Contents

- What "tools" does a lighting designer use? Controllable properties of stage lighting

- Angle

- Combine lighting angles

- Brightness

- Subjective impression of brightness

- Adaptation

- Visual fatigue

- Visual perception

- Emotional perception of brightness

- Warm and Cool Lighting

- Movement

- Rhythm

- Composition

- Focus of attention

In this chapter, we will briefly list the tools available to a lighting designer for creating the lighting design of a performance. In the following sections, we will return to these categories multiple times, as the goal of this book is to identify the most effective ways to apply them. We cannot determine which category is primary or secondary. Depending on each specific production and its unique conditions, any category can become critical to realizing your vision. Therefore, the order listed below is arbitrary.

In his book, The Method of Stage Lighting, published in 1932, McCandless identified four main properties of light that a lighting designer controls:

- intensity,

- color,

- form,

- movement.

Accepting what Stanley McCandless stated, it is necessary to expand this list, taking into account the modern advancements in theatrical technology and the evolved understanding of contemporary theater aesthetics.

- Angle

- Brightness

- Form

- Color

- Movement

- Rhythm

- Composition

- Focus of attention

Angle

Perhaps this is the most frequently asked question for a lighting designer: "from where should the light source be directed to illuminate a given object." The answer depends on the multitude of ideas the designer aims to achieve for that object. How fully should this object be illuminated, and how "dramatically" should it appear in the viewer’s perception. Often, these two objectives must work together but can also conflict with each other. The "dramatic" quality of shadows can be reduced by other sources that provide "full" illumination. The graphic nature of shadows is also a component of the composition.

Whenever we determine the position of a light source in space, we address a series of questions: is the light illuminating the object abstract or motivated? If motivated, then by what — is it the light of the sun, moon, a candle, a sconce, or an advertising billboard. If abstract, it means that in the viewer’s perception, this light is not associated with any existing light sources. At the same time, we must recognize that the angle of illumination also carries an emotional impact. Even in childhood, a face lit from below frightened us, evoking emotions of fear.

Based on the main directions, lighting can be divided into six basic categories:

- Frontal lighting – light directed straight at the object at the level of the viewer’s eye line

- Backlighting – light directed at the object from behind

- Side lighting – light directed at the object from the side

- Top lighting – light directed at the object from above

- Bottom lighting – light directed at the object from below

- Frontal top lighting – light directed at the object from the front and above, within 45 degrees from the stage plane.

Undoubtedly, this division is quite formal, since in the real conditions of the stage, there are numerous possible positions for installing fixtures; nevertheless, any lighting angle can be considered a derivative of those listed above. (For example, top backlighting, positioned behind / above.)

In terms of emotional impact, depending on the lighting angle, the following can be noted:

- Frontal lighting, due to the absence of shadows, appears uninteresting and dull. However, in certain situations with a powerful source, it can create a specific emotional effect.

- Backlighting, is described as mysterious and mystical.

- Side lighting, is usually very engaging and significant but feels quite abstract.

- Top lighting, is often perceived as mystical and mysterious, like backlighting, and can serve as a strong dominant element. It is frequently used to "press the scenic composition to the floor."

- Frontal top lighting, when positioned within 45–60 degrees, can appear quite engaging and clean. This is the optimal angle when we aim to ensure the best visibility of the actors’ facial expressions.

Considering these aspects, perhaps the most important thing is to understand that SHADOW is no less significant than LIGHT when the goal is to reveal the contours or form of an object. The interplay and balance of light and shadow provide the opportunity to achieve a sense of emotionally significant spatial volume and perspective.

Combine lighting angles

When illuminating an object to achieve the intended goal, you always use multiple light sources, combining various lighting angles. By maintaining a specific ratio (balance) of brightness among several differently directed sources, you emphasize the one that is key (primary) for you, reducing the brightness of the others, which serve as fill, in a certain proportion. It is understood that the effects of the primary lighting angles, when combined with others, will differ from their effects when used alone.

There is nothing worse than using too many sources with different lighting angles to illuminate an object — you will achieve brightness, and the object will be highly visible, but it will be dull and unengaging; you will ruin the picture. For this, follow the rule: "Necessary and sufficient." Minimalism in this matter is essential — "too much is no longer effective."

Combining lighting angles allows us to blend the sensations brought by different lighting methods.

Backlighting, as we have already noted, is described as "mysterious and mystical," and when used in isolation, it excellently highlights the form and contours of an object. However, in its isolated state, it can be used only once or twice in a performance. When combined with other light sources, it can transform the scene into an entirely different state. For example, in combination with high-quality side lighting and a small amount of frontal lighting, it can isolate the object from the existing scene and, in the viewer’s perception, bring the object closer to the audience.

- The direction from which the object is illuminated determines how the viewer will see it and how the object will appear.

- Lighting, depending on the angle, can be perceived (understood) by the viewer as FLAT or VOLUMETRIC, REALISTIC or MYSTICAL or STRANGE, as TRUE or FALSE.*

- The way the viewer assesses the quality of lighting on stage directly relates to what they observe in nature and the surrounding world.

- A single powerful light source can be highly effective due to its simplicity.

The dominance of one powerful directional source in a picture created by many other sources is often referred to as the "key source". The use of "key" light can also be exceptionally expressive.

Analyzing how a light source "functions" in the lighting design, depending on the angle of illumination of the object, the general conclusions are as follows:

- Light reveals and emphasizes form

- Uniform, equally bright lighting that ensures visibility is usually dull and unengaging.

- Shadow always emphasizes light.

- A large number of sources always leads to a loss of definition.

- A dominant "key" source is always expressively effective.

Brightness

Brightness is the amount of light energy reflected by the stage. The lighting designer manipulates intensity by selecting the types, power, and number of lighting fixtures used, and adjusts illumination by altering the supply voltage to each fixture. Brightness of light is a variable that can range widely, from faint flickering to the highest limit the eye can tolerate. In theater, brightness depends on the number and size of fixtures, as well as the use of dimmer banks, filters, shutters, gobos, and similar tools. Several factors must be considered when understanding the category of brightness.

Subjective impression of brightness

Illumination can be measured using various scientific methods, which in theater conditions may be of purely academic interest. The lighting designer is far more concerned with the subjective impression brightness creates for the audience: that is, not what the light is, but what it appears to be. A single candle on a dark stage will seem quite bright, while kilowatts of fixtures in a brightly lit setting will appear rather dim. Contrast is the primary measure of brightness. The color and texture of scenery, costumes, props, and the makeup on actors’ faces significantly affect the perceived brightness. The same brightness level will produce different effects in black or white settings.

Adaptation

As brightness changes, the observer’s eye adapts. The eye has a vital biological ability to adjust to different operating conditions. Thanks to this property, the visual system functions across a wide range of brightness levels: 10⁻⁶–10⁵ cd/m². When the brightness level in the field of view shifts, a series of automatic mechanisms activate to recalibrate vision. Adaptation should be viewed as the process over time of perceiving the transition from one brightness level to another. A bright scene will seem much brighter if it follows a dark one. However, after the eye adapts, it will "dim." Therefore, to maintain the sense of brightness, it may be necessary to gradually increase the brightness throughout the scene to counteract this "dimming" effect. Conversely, if the scene preceding a dark one gradually darkens, the viewer’s transition to "darkness" will be smoother, improving their perception of events in the dark scene.

Visual fatigue

The physiology of the human body is quite persistent. Just as muscles tire from intense exertion, the visual perception system fatigues from excessive strain. As a result of fatigue, sensitivity thresholds for both color and brightness decrease, reducing the efficiency of the visual system. Overly intense blinding light, prolonged very low illumination, or numerous abrupt light transitions can all cause viewer fatigue.

Visual perception

Many psychological factors influence how viewers perceive brightness, including the level of adaptation, brightness contrast, the brightness of the light itself, luminosity, and more. By manipulating brightness, we aim to provide a level of illumination that allows easy distinction of color, reflectivity, contrast, the size of an object, and its distance from the viewer. When crafting a scene, by arranging the perceived brightness ratios of different zones of the stage space in a specific way, we establish a hierarchy of objects in the viewer’s perception. We also control the sequence in which the viewer interprets (processes) our composition, knowing that the viewer always notices the most illuminated object first, then the less illuminated, and so on down to the darkest.

When addressing all these intriguing challenges, it is essential to remember that, above all, we must respect the audience seated in both the back and front rows of the theater. The farther the viewer is, the more light must be present on stage. Always remember and account for the "inverse square law." – Illumination is inversely proportional to the square of the distance. A viewer seated twice as far away will see four times less clearly.

Editor’s note:

If you move away from the light source by 2 times, the illumination decreases by 4 times (2² = 4). If by 3 times — by 9 times (3² = 9), and so on.

In the context of theater:

If an actor is illuminated by a spotlight, and a viewer in the gallery is seated 2 times farther than a viewer in the first row, then the eye of the viewer in the gallery receives 4 times less light from the same object.

This affects:

- contrast of scenes (the distant Westhampton Beach) (the distant viewer distinguishes nuances less effectively)

- choice of fixture brightness

- placement of spotlights (especially when lighting large stages and auditoriums)

Emotional perception of brightness

The tension and mood associated with brightness are determined by how comfortable the viewer feels in the given situation. Bright light enhances visual acuity, making viewers more responsive. The traditional rule "bright light for comedy" perfectly illustrates this.

Form

We have already briefly touched on the issues of revealing the form of objects on stage when discussing various lighting angles. The principle of illuminating an object directly relates to the form the viewer perceives. Here, we will address a slightly different aspect of form. An artist preparing to create a painting stretches the canvas onto a frame. The size and proportions of the canvas are no less important to them than the content of the future painting itself. The form of the canvas already carries a specific informational and emotional message. Similarly, for the lighting designer, relative to the boundaries of the architectural space, it is necessary to decide which volume of space should be utilized at each particular moment of the performance. Even if the scenographer rigidly defines the playing space, the lighting designer can always illuminate it entirely or only a specific portion of that space.

It is a well-known rule that the more light is focused on a single actor, the more they stand out, and the more the viewer focuses on the subtleties of their psychological performance. As we increase the size of the field of view, viewers, it can be assumed, broaden their attention to include the influence of the surrounding environment — social, symbolic, or even cosmic. Drawing parallels with painting, for instance, a narrowly illuminated actor is like a portrait. Large illuminated areas resemble a landscape or genre scene. Drama typically involves a conflict between the individual and their environment. Personal conflicts are usually internal. The same principle applies to light: the wider the space, the broader the range of issues encompassed. In a particular style of performance, the size of the illuminated space may vary depending on the shifting nature of conflicts throughout the play.

Color

In The Theory of Colors, J.W. Goethe wrote: "color is a product of light that evokes emotions." When we say: "blackened with grief; reddened with anger, turned green with envy, turned gray with fear," we do not take these expressions literally but intuitively associate a person’s emotional experiences with a means of expressing them through color. Any color within the visible spectrum is, in principle, available to the lighting designer. Color on stage is the result of blending colored light with the color of an object. Objects are visible only because they reflect light to the eye. Subtle tones of colored light can highlight actors’ faces or establish the overall color tone of a scene. Natural or stylized color is used to emphasize, alter, or achieve the desired color tone of costumes and scenery. Fundamentally, all light is already colored. Even the most powerful light source — the sun — we only conditionally perceive as "white," but when broken down, it reveals the full spectrum of colors.

The effect of color on a person has long been observed: color influences all their physiological systems, activating or suppressing their functions; color creates specific moods and instills certain thoughts and feelings. The impact of color can be categorized as physiological, psychological, and aesthetic; to these, we must also add color associations, semantics, and the symbolism of color.

Bright, saturated, or rich dark colors can be highly dramatic; they are typically used to signify or convey to the viewer a meaning tied to the associative or symbolic significance of the color. For example, red might be interpreted as "passion" or "blood," blue as "peaceful" or "romantic," green as "envy," and so forth. In any case, the meaning of saturated colors is highly significant.

Light, pastel colors are no less effective but are less imposing. Colors in light tones are more often used, for instance, to depict the natural setting in which the stage action unfolds, such as mimicking the light of a sunny valley or a moonlit night. Additionally, certain colors are employed to enhance the color and texture of facial skin, costumes, or scenery. Such lightly tinted lighting is generally categorized as "cool lighting" or "warm lighting."

Warm and Cool Lighting

When observing an object’s illumination in nature, its volume is always revealed by the balance of warm and cool lighting. We see one side illuminated, for example, by warm sunlight, while the other side is always lit by cool light reflected from the sky. This creates a stunning interplay of light and shadow; in nature, shadow is always cool. It is important to understand that, like brightness, the warmth or coolness of a color is always relative to the adjacent color used. In different combinations, the same color can appear either warm or cool. Typically, in a well-crafted, balanced scene, a "clean," unfiltered beam will look lifeless and harsh.

By selecting colors and composing your palette of "warm" and "cool" tones, you create the palette with which your scene — the performance — will be painted. Do not overlook the principles of harmony; the combination of colors is the language through which we communicate with the viewer. It is necessary to remember:

- All light has color

- Color is a powerful tool for creating atmosphere and mood

- Color is used to indicate the location of the action, time of day, and season

- Light colors can also create mood and atmosphere but do so more gently

- Saturated color can easily overwhelm or oversaturate the stage picture and must therefore be used with great care

- Colors carry symbolic and semantic significance and can be utilized as a signaling device

Movement

A solitary beam of a spotlight moving through the stage space is, in itself, a sufficiently potent expressive tool. You all vividly recall the famous act by the renowned clown Oleg Popov, who performed on the arena with a spotlight beam as if it were a partner. The great Gordon Craig, in his Hamlet, used the movement of a beam to depict the appearance of Hamlet’s father’s shadow. We are not addressing here the routine task of follow spots illuminating soloists and prima donnas. Visible moving spotlight beams can alter scenography, perspective, volume, and transform the stage space. A moving illuminated area is also a powerful emotional and scenographic instrument.

In the past, this was always a rather complex technical challenge for theater. Without dynamic, controllable spotlights, it could only be accomplished with a substantial number of light sources directed in specific ways. By smoothly adjusting the intensity levels, fading some sources and introducing others, it was possible to create a sense of movement of the illuminated area from the footlights into the depth, and so on.

The advent of dynamic automated fixtures, increasingly transitioning from show productions to theater, now enables the relatively straightforward realization of dynamically expressive lighting concepts. Movement is a factor of time, and the speed of movement and changes in the configuration of the illuminated space are primarily dictated by the dynamics and tempo of the stage action. Simultaneously, this movement can also establish the dynamics of that same action.

Rhythm

A factor directly tied to time and determined by the rhythmic structure of the stage action. The tempo-rhythm of changing light cues shapes the dynamism of how the stage action is perceived. The rhythmic structure of shifting light cues is directly constructed based on the production concept of the performance, rooted in the original dramatic or musical material (score).

The dynamic evolution of the emotional perception of the stage work’s structure pertains not only to the acts but also to each individual moment of the action. A popular technique in the 1960s and 1970s for heightening drama — activating a "strobe light" or the smooth, multi-minute transition of "dawn on the Moscow River" in Mussorgsky’s opera Khovanshchina — exemplifies the determination of the rhythm of stage action.

The frequency and contrast of changing light scenes on stage, even amidst the static nature of other performance elements, establish the rhythmicity of the performance’s perception.

Composition

Theatrical lighting is "artistic" primarily because it demands the creation of a unified, cohesive dynamic image within the performance, one that emerges from and is intricately linked to the structure of the complex phenomenon of the performance. All the expressive capabilities of lighting design — in crafting pattern, form, and perspective — are subordinate to the idea and purpose of the performance. Knowledge of compositional principles is as essential for the lighting designer as it is for any artist whose work is oriented toward visual perception.

Undoubtedly, the lighting design of a performance is directly dependent on many elements of the overall production solution, over which the lighting designer may have no control. The director, actors, and scenographer, along with the costume designer, can collaborate and adjust elements to support the compositional conditions. Even a photographer can shift their shooting angle to perfect the composition. The lighting designer, in this sense, cannot even alter the audience’s viewpoint. The scenographer and director may agree on a compositionally advantageous position for an actor, but if the action requires the actor to move to another spot on stage, the composition is disrupted.

All elements of visual composition are interconnected and influence the overall image. No compositional element can "function" without lighting, and only light can bring all elements into final harmony. Theater is predominantly oriented toward visual perception, and the lighting designer is the final arbiter of what and how the viewer sees. The only tool at the lighting designer’s disposal is light. Composition can be controlled solely by enhancing the illumination of certain visible parts or plunging others into darkness, expanding or contracting the field of view. This is a significant responsibility, offering the opportunity to either enhance perception or, conversely, undermine the perception of a composition crafted by others.

With this understanding, when working on the composition of lighting design, the lighting designer must consider that audience members view the stage from various positions, and a perfectly balanced composition for a viewer in the seventh row may not be equally striking or flawless for a viewer "in the gallery."

Focus of attention

Formally, this category might not have warranted its own section. We know that the most highlighted, bright zones and objects are the most appealing for the viewer to observe. This is what the viewer looks at first. Typically, they form the center of the composition. For easel painting, this is indisputable. In theater, however, due to the dynamism of the events — where the entire composition can shift with the slightest movement of an actor — and the relatively wide range of audience seating positions, this means that the constructed composition will be interpreted differently by a viewer in the 8th row versus one on the balcony. It is necessary, using the properties of light and color, to anticipate and plan how the viewer will observe (visually interpret) the stage action.

Light is one of the foundational elements of nearly all "visual" compositions. And, of course, among all visual forms, light is the most intangible tool. In any stage performance, light is a more abstract element than any volumetric object placed on the stage, which tends to draw significantly greater visual interest.

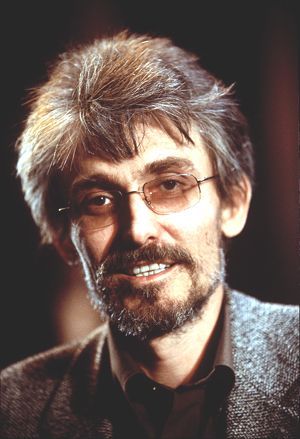

More about the author’s biography

Other articles in the series:

- New articles will be available soon.

! All rights to the original text belong to the heirs of Vladimir Lukashevich !

The text is published with the consent of the copyright holders.

Alex Deno

Editor. Founder Sundrax, PhD

The material is published with respect to the author, exclusively for educational purposes.

"In memory of the talented artist who left a significant mark on world theatrical art..."